It’s been just two and a half years since the launch of ChatGPT introduced the term “generative AI” to the wider public. It marked a watershed moment in technology, a once-in-a-decade revolution that will prove as broadly impactful as the creation of mobile phones or the internet itself.

Every powerful new technology holds out the promise of significant benefits but also the potential for misuse. Generative AI is no exception, and arguments over its potential benefits and harms are likely to continue for the foreseeable future. One key point of contention is the relationship between AI, truth, and misinformation/disinformation.

In an age where any form of evidence, from the written word to full-motion video, can be persuasively faked, how are we to find and assess the truth?

What Generative AI Is

“Artificial Intelligence” is a fairly generic term. A more useful definition came from the famous English mathematician Alan Turing. He argued that if a blindfolded person couldn’t tell whether they were conversing with a human or a computer, that computer could be considered to display artificial intelligence, with intelligence defined as an ability to make practical application of data and knowledge. That’s known as the “Turing Test,” and generative AI products excel at this. So what is generative AI?

There are many approaches to AI, and one is called machine learning (ML). In simple terms, an algorithm is trained on a large volume of data until it can reliably process the data and provide usable outputs without human guidance. Generative AI products use what’s called “supervised” machine learning. This means the model is trained on data that has already been labeled by humans and learns to apply those same labels to unknown data by extrapolating from what it already knows (much as humans do).

In the case of ChatGPT or other text-based models, the training data consists of large quantities of text that might be categorized (to pick just three examples) as poetry, academic papers, or business communications. For image-based models, training data consists of large volumes of images labeled by humans. The fully trained model can then generate novel content, drawing on that training, which is why it is called “generative” AI.

A Quick Review of How AI is Being Used

Generative AI trained through supervised machine learning is fundamentally an optimizer. Given a set of inputs, it can be used to predict and control problems, identify inefficiencies for elimination, provide augmented capabilities, and/or improve decision-making.

In practical terms, some of the ways generative AI is already being used include:

- Improved guidance systems for driving assistance features in vehicles and for fully autonomous vehicle operation.

- Writing and prototyping code to speed the development process.

- Generating working drafts of documents and reports.

- Extracting actionable information from large volumes of unformatted data, such as books, databases of academic papers, or emails.

- Creating photorealistic images and videos of things that do not exist or combining real-world imagery with AI-generated imagery.

The potential for growth in AI is significant. McKinsey’s 2024 Technology Trends Outlook identified generative AI, applied AI, and industrial machine learning as its top three tech trends, collectively attracting well over $100 billion in equity investment. Among companies responding to McKinsey’s survey, 74 percent indicated that they were at some stage of deployment (from experimentation to fully scaled) with generative AI and applied AI. Furthermore, 63 percent reported similar initiatives in the field of industrial machine learning.

The Impact of Generative AI on Misinformation and Disinformation

For all its promise as a useful and productive tool, generative AI – like any other technology – is susceptible to misuse or abuse. Scammers, for example, were quick to realize that generative AI’s power as an optimizing technology could be applied to phishing attacks. North Korean state actors have used AI tools to create fake identities, gaining remote employment in sensitive positions with US firms. They can even convincingly replicate the writing style or voices of targeted individuals in key positions, creating the potential for high-value scams or security breaches.

Though these are troubling examples, generative AI poses a more fundamental threat. AI tools are now capable of generating convincing output in the form of written documents, images, and videos. It can simulate a legitimate news story from a major site or even create a video showing a celebrity or politician engaging in unsavory activities. Whether this faux content is spread deliberately by malicious actors (disinformation), or unwittingly by those who believe it to be true (misinformation), it poses the same question: When anything can appear true, how is it possible to recognize those things that genuinely are true when we see them?

By throwing the very concept of objective truth into doubt, generative AI is undermining our ability to function as a society.

Recognizing Truth in the Age of Generative AI

So how can we recognize truth in an age of AI-fueled misinformation and disinformation? Even at its most basic, truth is a high-dimensional concept. True things — things that have an objective reality — have many dimensions. Simulations have only enough to be persuasive in their context and can be detected if they are subjected to determined inquiry. In short, while no one test may be adequate to distinguish between truth and mis- or disinformation, we have a suite of tests, tools, and techniques that individuals, institutions, and our society as a whole can draw on to differentiate them.

These tools include:

Detection

While AI and machine learning can be used to generate almost any kind of content, they can also be trained to detect AI-generated content. These tools are currently in their infancy and have high error rates (both false positives and false negatives), so they’re best thought of as a “first-pass” tool to flag articles or images for further review. Like the ongoing battle between malware creators and malware detectors, the creators of AI detection tools will be locked in a game of cat and mouse with AI creators for the foreseeable future.

Authentication

Authentication is any means of linking a digital entity (any output, from an email to a purported news story), back to its origin with an identifiable physical person. For example, security breaches or financial scams relying on “spearphishing” attacks purporting to come from an executive can be thwarted by requiring biometric data or other forms of authentication, such as a hardware key or one-time passcode, before sharing sensitive data or transferring large sums of money. A predetermined spoken code word or password provides similar protection against voice-cloning attacks, in which AI is used to create a persuasive impersonation of an executive’s voice and manner.

Digital Signatures and Watermarks

Digital signatures and watermarks can be deployed to 1) verify the integrity of data (or the legitimacy of a communication); and 2) proactively identify an output as the product of AI. Digital signatures use cryptography, requiring the creator and reader to each have access to verified digital keys, enabling the creator to encrypt a file and the reader to decrypt it. The less sophisticated watermarks used to identify AI outputs are encoded or embedded in the output, though these are less secure and can be tampered with.

Applying Critical and Philosophical Criteria of Truth

Technology is not the only tool that can be applied in the search for truth. Critical thinking and contextual tools have played an important role in that quest for thousands of years. Some of those intellectual tools include:

- Authority: We accept some things as true on the basis of their source. The information on a driver’s license is likely to be true, for example, because we know that the DMV has strict criteria for verifying that information.

- Consensus: If multiple sources (the more varied, the better) agree on the truth of something, it is more likely to be true. The higher the level of expertise within the group forming the consensus, the more valuable this indicator becomes.

- Coherence and consistency: Do all parts of the thing under review (a document, an image, a purported news story) seem coherent? Is the language natural? Are the arguments well-constructed and lucid? Do all parts of an image show the same level of detail, lighting, and color saturation? If those tests fail, fakery is more likely.

- The test of time: This can be thought of as a “consensus that continues over an extended period.” Consider nutrition as an example. While questionable fads and supplements come and go, the benefits of a diet high in fresh produce and whole foods have held up under decades of scrutiny.

This is a small but representative sample of the critical-thinking tools that can help individuals and organizations to navigate an environment rich in mis- and disinformation.

Provenance

Verifying the provenance of data is a crucial step in ensuring data integrity. Provenance is simply the traditional “six Ws” of inquiry (Who, Where, When, What, Why, and hoW), as expressed in metadata, or data about the data. This can be difficult to assess at the enterprise or institutional level, where data passes through multiple layers of processing and manipulation. Blockchain technology can be useful here, creating a viewable and tamper-evident record of changes made to the data over time.

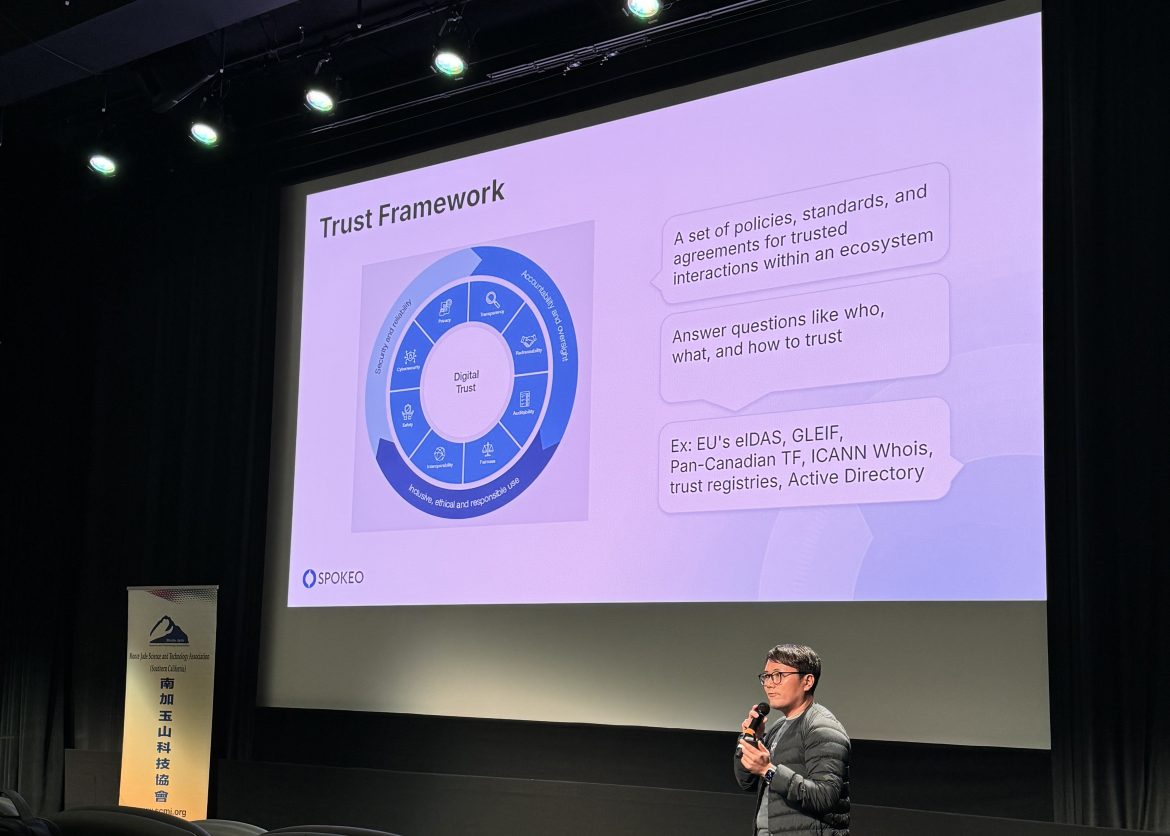

Trust Frameworks

Another powerful tool for establishing the truth of information is through the formation of, or participation in, a “trust framework.” This is a set of policies, standards, and agreements that create an ecosystem where interactions can be innately trustworthy. It requires a high level of accountability and oversight, as well as strong security measures, but can be very useful once established and operational. Examples include the European Union’s electronic identification and trust services (eIDAS), the Global Legal Entity Identifier Foundation (GLEIF), and ICANN’s Whois registry of domain name owners. Information, services, and identities accessed through these channels can be considered accurate and verified for most purposes.

Education

One final and important tool in the search for truth is education. In the case of AI, this is especially important because of the widespread fears currently surrounding the field. The likelihood of AI taking over, Terminator-style, is relatively low. The likelihood of AI eliminating some kinds of jobs is higher, but we’ve seen this before. Blacksmiths and livery stables largely went away when automobiles replaced horses, but mechanics and garages sprang up to replace them.

Educating people about AI – how it works, what it does well, and what it does poorly – is an essential step toward putting those natural fears behind us and regarding it as a tool like any other. Understanding its strengths and limitations will help us apply it intelligently to the world’s problems and also to recognize negative outcomes when we see them.

Truth is Spokeo’s (and Everyone’s) Business

Our shared consensual reality, or objective truth, was already under attack before the advent of generative AI. The same tools used to personalize your viewing recommendations, playlists, and impulse purchases also play out online, as algorithms determine which information and opinions you’ll be shown. Generative AI simply made it possible for more players, each with their own agenda, to promote their own versions of the truth more effectively and on a greater scale.

Now more than ever, expertise in assessing the truth is a crucial skill set. More than that, it lies at the core of Spokeo’s business model: our users are seeking objectively accurate, verified, truthful data. In fact, we use most of the principles and techniques described above, in one way or another, in pursuit of accuracy. For example, we examine metadata for signs of tampering and weigh our model in favor of data from authoritative sources. Similarly, as we approach two decades in the data business, we also have history with our data sources and have been able to assess which sources and which data remain consistent over time.

At Spokeo, we believe truth is important. We do our part to try to ensure that the data we aggregate – about you, me, or anyone – is as accurate and truthful as it can be. For each of us as individuals, applying the same tests to new information before choosing to believe it or not is equally important. Maintaining a base of verifiable truth is a goal worth fighting for: it fosters trust and will help us build a better world.

Harrison Tang Bio

Harrison Tang is a prominent entrepreneur and business executive known for his remarkable contributions to the data industry. In 2006, he co-founded Spokeo, a people search engine, and currently serves as its CEO. Harrison has received prestigious awards, such as the Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year Award in Los Angeles in 2015. Spokeo has also been featured on various “fastest growing” and “most promising” lists, such as those by the Los Angeles Business Journal, Forbes, Deloitte, and Inc.